The New Ludics in Today's Digital Art

by Patrick Frank

The art world has a history of scorning digital art, often because it has been seen as a product of a pact with the devil. In the early days (the 1960s) digital artists had to ingratiate themselves with the research labs of large corporations that were among the few owners of the bulky and expensive equipment. After the PC desktop revolution (the 1980s), artists still had to learn certain kinds of geeky "non-artistic" technical skills.

Maybe scorn is too strong a word; how about "relegate," which means almost the same thing in this world. Now we usually express disinterest in more Seinfeld-schooled ways, such as the qualified "not that there's anything wrong with that." And digital art is still regarded as a separate category, rather like photography was in its earlier days, meaning that it has its own devoted galleries, museum departments, exhibitions, historians, etc. Well, this exhibition brings good news: It shows a twofold pathway out of digital art's marginal status. One way is through easy accessibility for display; once you acquire these works that are created for the iPad, you can just carry them around with you. You have your own originals. The second and more important way out is through the contents of the actual pieces. All across this exhibition, these works engage in a certain kind of play that unites the viewer with the work in ways that I am calling the New Ludics. Discussing one work by each of the eleven creators in this show, I am going to make the case by examining them against three definitions of play, as we take three increasingly large leaps backward into history.

Note at the outset that ludics is not the same as Luddites; it is rather the opposite. Ludics comes from the Latin ludere, to play. In contrast, a Luddite is a follower of the early 19th-century labor activist Ned Lud, who led rioting workers to destroy the cutting-edge, water-powered machinery that threatened their jobs as weavers. Executive summary: even a Luddite can enjoy the New Ludics on view here.

I

Our first leap backward is to the 1993 Super Bowl game. The Dallas Cowboys did not exactly upstage Michael Jackson's halftime show that year, but in a post-game interview explaining the team's victory, winning coach Jimmy Johnson did introduce a concept to the world that had previously lived in psychological circles: Flow. The Cowboys got into a flow.

At its most basic level, flow is what you feel when you are involved in an activity that is sufficiently engaging and goal-oriented that you forget yourself for awhile. The activity is not difficult enough to provoke anxiety; nor is it so easy that boredom sets in. The concept was most clearly described by Romanian-born American psychologist Milhaly Csikszentmihalyi. Flow, he said in an interview in Wired magazine, is "Being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one." Maybe it's easy to see how a pro football team can get into a state of flow and win the Super Bowl, but Csikszentmihalyi (chick-zent-me-hi-ee) developed the concept while watching students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago similarly lose themselves in the creative process. Effortless, continuous focus and action characterize flow. "Moments such as these," he wrote, "provide flashes of intense living against the dull background of everyday life." Because such moments involve no practical needs, art is an arena uniquely suited to generate flow.

Several artists in Poetic Codings have created works that function better than football to put viewers into the state of flow that Csikszentmihalyi described. The iPad itself, as a delivery vehicle, encourages this sort of mental state by its intimacy, because the screen allows the best viewing for only one person at a time. More important, certain iPad creations allow significant input from viewers which has a determinative impact on how the final product appears. Scott Snibbe's Gravilux is a case in point. Gravilux allows us viewers to set up an initial grid by choosing the color, size and density of dots. We then control the speed and direction of their succeeding on-screen motion by tapping or swiping. We can program the grid to slowly evolve in a chosen direction, or collapse it into chaos immediately on our touch. Repeating the touch takes the chosen process further. We can even begin with a word or phrase in Helvetica type, and then distort it in the same myriad ways.

Scott Snibbe Gravilux

Jody Zellen 4 Square

|

|

The desire to learn how to take advantage of the app's features, combined with the hope to create something visually interesting, are the twin goals that set the boundaries of our interaction with this app. Such goals are crucial to flow, as opposed to merely random choices quickly lead to boredom. We might compare the interactivity of Gravilux with the mere surfing of websites. Csikszentmihalyi pointed out that such directionless surfing is antithetical to flow: "Unfortunately, most sites are built like a cafeteria. You pick whatever you want. That sounds good at first, but soon it doesn't matter what you choose to do." Viewers who need a more passive experience with Gravilux can select a piece of music from their personal library, set the grid parameters and then watch the music set the process in motion as they listen. After trying this function with music ranging from grand opera to country, I find that it works particularly well with modern music, such as the string quartets of Steve Reich, or John Cage's pieces for prepared piano. The flow that Gravilux sets in motion is one that we have created.

Snibbe's apps are all quite abstract, but exhibition organizer Jody Zellen creates similar flow opportunities with more thematically focused imagery. Her app 4 Square, for example, allows viewers to select input from four different banks of images arranged in quadrants: solid colors, groups of three words, and two sets of digital drawings by the artist. Tapping a quadrant randomly selects another image from that particular set, and viewers can arrange the quadrants in any order. Though randomness is built into this app, the imagery coheres around a theme of modern urban life. The flow of this piece comes from our natural tendency to look for meaning in conjunctions. I recently pulled up "estate luck good," for example, alongside two drawings of hunched-over figures and a rich green field. Against the backdrop of all the recent public debate about wealth distribution and tax policy in connection with our various fiscal cliffs, I see in this frame a comment about the top one percent, middle-class people concerned about declining real incomes, and a square that reminds me of the color of money. Tap each quadrant even once, and the entire constellation changes. Not all such conjunctions cohere thematically as much as that one seemed to, but then maybe I am not creative enough to see more possibilities. In any case, the app rewards viewers who have an attitude of openness toward the "thematic clouds" that 4 Square prodigiously generates.

|

"Prodigious generation:" That phrase seems an apt description of many of the works on view in this exhibition.

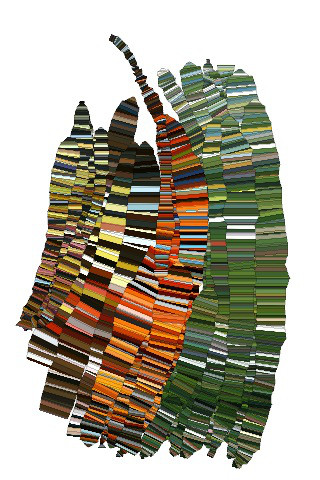

Jeremy Rotsztain

PhotoRibbons |

|

Jeremy Rotsztain's PhotoRibbons enables a similarly focused interaction, but this time with our own photographs as a basis. Dragging a finger across the photo creates ribbons of colors divided into segments. Viewers control the color scheme, the width of the ribbons and the sizes of the segments. PhotoRibbons thus combines a painting app with a photo viewer, and allows us to melt our photos into abstract messes, or, with less intervention, into amusing caricatures or painterly do-overs. Several steps of undo and redo are built in, so that viewers can "perfect" their technique, or alter it for each type of photo. We apply artistic transformations to our snapshots. As Csikszentmihalyi noted, creativity is an excellent way to generate flow; in the Wired interview he likened it to playing jazz. The creators of these apps have built in a high degree of viewer input, sharing their creative responsibilities with us.

The interactive works in this exhibition update an undercurrent in modern art that began with Marcel Duchamp's Rotary Glass Plates, in which the viewer is instructed to start the work with a switch and then stand at a certain distance to view its effects.

|

This trend got a large boost in the 1960s as some artists sought to de-mystify the creative process, part of an attack on the notion of the artist as solitary genius. Hence the work of artists such as Lygia Clark, who made abstract metal sculpture with hinges that the viewer could manipulate, folding the work into a desired shape. In the same decade, artists of the Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel (GRAV) created viewer-activated works, works that changed their appearance depending on the viewer's location, and items such as wearable lenses that viewers could take outside the gallery. Since the 1980s, a great deal of digital art has taken advantage of interactive technology. The present works are the most portable, and in many cases the most elegant of works in this vein yet created. Duchamp said that no art work is complete without a viewer; the interactive works in this exhibition take that statement to its logical conclusion, because viewer input is not merely desirable but required.

II

Our second leap backward will take us from the Dallas Cowboys to the modern thinker who placed the most importance on play in culture, Johan Huizinga. In the 1938 classic Homo Ludens, he named three characteristics of play: It is voluntary, it is not ordinary life, and it has well-delineated boundaries (rules) that separate it from such ordinariness. Huizinga found the play-instinct all across cultures, from ritual dances of tribal groups to ancient Greek singing contests, to our contemporary doodling through a boring meeting. And play even predates human culture, as we see when our pets frolic. Play, he wrote, is basic to life itself.

Yet Huizinga was more comfortable finding the play-element in art forms other than the visual. Dances, dramas, poems, and competitions of various kinds seemed more play-like to him than visual art with its skills and premeditation. "This quality of handicraft, of industry, even of strenuousity in the work of plastic art obstructs the play-factor," he wrote. When artists compete with one another, as they did in mythological painting contests, in the classical competition for the Prix de Rome, and in today's public art grants, creativity joins with more traditional play forms, and Huizinga sees more ludic forces in play. But this is exactly where the artists in this exhibition enter the game, decisively. Several creators in this exhibition have either used their skills to establish the boundaries for a play-zone for us to inhabit, or they have shown such a playful attitude toward cultural customs and symbols, that were Huizinga alive today he would surely be writing this essay in my place.

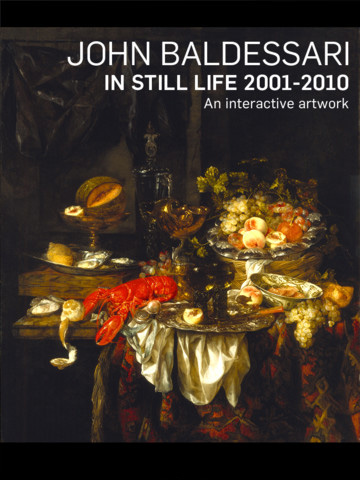

John Baldessari

In Still Life

John Carpenter

Stars

Jennifer Steinkamp

Dance Hall Girls

|

|

To begin this consideration with the most obvious case: For the app In Still Life, John Baldessari set up a digital version of an actual 17th-century Dutch table-top painting, so that we can rearrange all 38 of its compositional elements at will on our screen. We can pile the goblets atop one another, deploy the fruit in a perfect circle in midair, try to improve on the original creator's balanced composition, or toss everything, oysters, lobster, dishes and all, into a messy heap on the floor. And when we have done our best, whatever that might mean, a tap on the Share command sends our creation to one of several dedicated web pages, where the playful attempts of others to do the same can be easily called up and viewed. Working with this app affords several hours of stimulating and irreverent fun.

If Baldessari lets us activate the play element with a fingertip, John Carpenter's Stars demands our entire body. This work combines a motion sensor with a digital projection of the night sky, so that our physical movements influence the location and paths of various projected heavenly bodies. We can wave our arms to coax them slowly across the space, create ripples and currents for the stars to ride, or merely flick a few shooting stars into existence. And when we still ourselves or move away, the original scene reorganizes itself before our eyes. The distortion of scale inherent in the suggestion that we can push the planets around, even as a projectionon a wall, feeds novel concepts into the imagination. We rearrange the cosmos like gods, but gods of a virtual realm.

The organic feel that Stars generates springs partly from Carpenter's previous studies of wave forms. Jennifer Steinkamp similarly studied organic motions, but then she mostly ignored them when she created the lilting movements of the flowers in her digital video installation Dance Hall Girls. Using the same software that Hollywood animators use, she envisioned this work as a suite of pieces, each devoted to a single species of garden flower. The imaginary wind that impels their cycle of motions lies somewhere between the natural and the digitally conceived.

Her disinterest in duplicating natural phenomena finds a parallel in her ironic attitude toward gender stereotypes. The title of this piece comes from the Western-movie phrase describing women in the employ of the saloon-keeper who dress up and entertain the male customers, encouraging them to order more rounds, as they themselves drink iced tea brewed to the shade of bourbon. Steinkamp said that she found the phrase "sort of funny and sexist." In this piece, she wades deep into the realm of stereotype, saying, in effect, that if you think of women as sweet-smelling and colorfully decked-out objects for delectation, then here you have some. But Dance Hall Girls is, of course, a send-up of such antique notions. This work is a postfeminist version of an art subject that traces back to Imperial Chinese bird-and-flower painting and forward to still lifes and to Georgia O'Keeffe. The play element of this work comes from its dancelike motions, bright colors, and, most important, from the mocking and mordant attitude of the creator. Huizinga noted that the play-function in culture often included the notion of satire, in cases such as, he wrote, "the public skits and scurrilous songs which formed part of the feasts of Demeter and Dionysus."

|

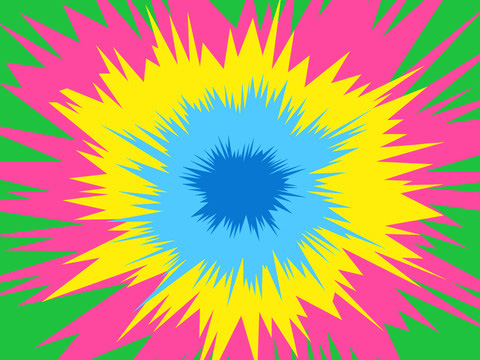

Rafael Rozendaal

Hybrid Moment |

|

Rafael Rozendaal's Hybrid Moment is an app-based version of a hilariously simple 2009 website of the same name. Both works fill the screen with a cartoon explosion that radiates as long as your battery lasts in garish colors. We influence its pace by tapping; closer to the center slows it down, near the edge speeds it up. The web-based version can be more dizzying, because desktop computers are faster than present iPads. But the iPad version introduces the chance to tilt the screen and cause the blast to rotate. Late last year, Rozendaal expressed frustration with the art world's elitism. He wrote on his blog, "The art world uses intimidation to achieve its authority: Intellectual intimidation (you're not smart enough to enjoy art), Financial intimidation (you're not rich enough to enjoy art)." After you have paid the 99 cents to acquire this work, even a 15-second encounter will likely prove to you that Hybrid Moment avoids both of these pitfalls. And it does so with a light-hearted and playful attitude.

|

III

Our third and final leap backward will take us to 1794, when a German playwright tried to redress the wrongs of the French Revolution. Like many thinkers, Friedrich Schiller welcomed the goals of that revolution— liberty, equality, and such— even as he deplored the violence and chaos that accompanied their dawn. The revolution had highlighted a split in human nature, he thought, between our moral impulses and our physical needs, or to put it another way, the intellectual and the emotional/sensual. The intellect— Schiller called it the "form-drive"— seeks order, balance, and stability. The emotions and the senses, on the other hand, which Schiller called the "sense-drive," seek imagination, freedom, and spontaneity. In a viewer's aesthetic contemplation of works of art, Schiller thought, the gulf is overcome. The organization of the work appeals to the form-drive, while the sensory aspects (color, texture, expression) draw our feelings and emotions. His Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man can help to illuminate many works of art from various times, but they are of particular use in highlighting the importance of several works in this exhibition, because Schiller held that aesthetic contemplation arouses a third drive that can harmonize our need for order with our sensuous desires: the "play-drive." The play-drive that the Letters expose is at the root of the ludics that characterize this exhibition.

For Schiller, play was not merely fun, though it includes that. Nor is it even necessarily interactive, requiring our conscious input. Play may engender fun or interactivity, but it need not do so because play is at root a mental state in which our various faculties are liberated from constraint. Contemplating a work of art activates the play-drive when reason, imagination, and feeling all work together in the viewer's mind to generate a state of free association and inner liberation. Schiller wrote, "it is precisely play and play alone, which of all man's states and conditions is the one which makes him whole and unfolds both sides of his nature at once."

Casey Reas

Signal to Noise

|

|

Signal to Noise by Casey Reas affords just such an opportunity. He created this work by recording a television broadcast and subjecting it to digital distorting operations. Reas selected the television show almost at random, from an actual over-the-air broadcast received through a rabbit-ears antenna. He then wrote software that randomly generates distortions of the input, shattering or overlaying it with grids of various density, using colors from the source material. These distortions play out in a potentially infinite sequence. His goal, he told me, was "to take something not very interesting to me, and make it interesting."

When we apprehend this work, we first confront a welter of sensory input: Squares and rectangles in multitudinous colors dance across the screen, in patterns that change at one-second intervals (the average shot length of many television shows).

Behind it, we can dimly discern the moving forms of the TV show that provides the substrate. Our rational faculties attempt to see patterns or rhythmic repetitions; they may also attempt to recognize the source material (which Reas says is irrelevant to the final work). At the same time, our senses bathe in the sheer intensity of the projected display, which nearly fills our field of vision. Signal to Noise amounts to a hyper-transformation of the most banal input, processed with the latest software. It enables imaginative play of a very contemporary sort.

|

Lia

Sum05

Jason Lewis

Bastard

|

|

Signal to Noise is exceptionally intense, but play can also occur at more measured pace, as we see in the iPad app Sum05 by the Austrian artist Lia. One tap sets the work in motion, as several moving dots begin to draw curving lines that seem to grow organically. We control the number of lines, their color, and their overall direction by where we tap and how we tilt the device. What emerges is a visual spectacle on a small scale, as sinuous curves trace paths across the screen, interrupted by obstacles that the software randomly implants. The app seems to create organic growth of an interestingly irregular sort, as a few lines break out of the parameters that we established and dizzily create their own jagged path. An excellent way to use this app is to set the device up at an angle, tap at what you think is the right spot, and watch what happens. The rapid evolution that we see suggests parallels to other sorts of organic growth, such as the weeds in your garden, or, on a larger scale, the evolution of species. Such a combination of pure visual interest with deeper reflections is at the heart of the play-drive.

Two creators in this exhibition have designed apps that work with text in radically new ways. Jason Lewis's app Smooth Second Bastard is a poem that the viewer activates by touching the screen. Each touch brings up a line of the poem, which floats across the screen as long as the viewer's finger holds it down. Releasing it shatters the line into pieces that grow and recede. Releasing a line before it fully appears causes it to collapse again and disappear; rapid tapping repeats a line. Thus, we can view the poem in our own way, bringing each line up to provoke its own ruminations before we deposit it and move on to the next. As the lines of poetry gradually surface and decay, they leave a residue of earth tones that forms a slowly moving, abstract composition. This is an analog to the memory traces that time-based experiences of all kinds leave as they unfold. These programmed characteristics, visually absorbing in themselves, amount to an added superstructure of form over the content of the actual poem, which deals with the theme of otherness. "Are you from around here?" the poem asks us near its beginning, before proceeding to question its own definitions. "A story lies amongst the curves and lines / Waiting to be told," we read. And the unfolding of the story is entirely in our hands.

|

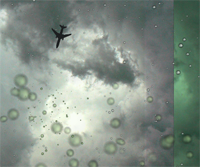

Erik Loyer

Strange Rain

|

|

Erik Loyer's Strange Rain is similarly word-based, but its accompanying imagery takes us into completely different realms. Opening the app seems to turn your iPad into a skylight that collects raindrops on a cloudy day, complete with sounds. Loyer programmed several ways for us to experience this app, with varying amounts of text (or none at all), and several possible musical accompaniments. The most involved navigation takes us into the mind of a man in a family crisis, who goes outdoors in the rain to sort out his thoughts; we bring up the thoughts by tapping. On occasion, our taps also cause the frame to reset itself with square splashes of color as passenger jets in silhouette pass low overhead. If these "resets" sound surreal, they are; joining them with the cinematic realism of rain falling toward us is an extremely evocative environment for the unfolding of the ruminative and thoughtful story that Strange Rain tells. Its connection to play is obvious from the fact that you can register your progress through its various levels by signing onto the iPad Game Center, a privilege that I have not yet accorded to myself. Instead, after you have navigated this app's various levels, I suggest that you prop up your iPad on your kitchen counter one evening as you cook dinner next week, and open the start screen with its sky-view to run by itself; all of this app's rich associations will stay with you.

|

The Game Center option in Strange Rain leads us to consider how closely any of these app-based digital works approach the concept of the video game; the latter are, after all, a form of play, and many of them show immense creativity. Yet large differences surface instantly. Many video games demand and improve the eye-hand coordination of players; our apps in this show have no such goal. Also, for all of their novelty and technical sophistication, many video games fall into scripts that are positively hoary with age: the chase, the race, the rescue, the ordeal, the contest of skill. The goal-orientation of such digital games may produce flow, but not of the aesthetic sort. The goals of the apps in this show are all heavily weighted toward formal experimentation. They have no goal other than aesthetic. Our input either guides the unfolding of a story or creates a novel visual experience. Even the apps that have the deepest thematic content lead us to absorbing aesthetic engagement that is foreign to most video games.

In conclusion: Have these digital artists made a pact with the devil? No more than any other artist. Yes, creating digital art still requires certain technical knowledge and skill, but I hope that the accessibility and elegance of all of these creations puts the epithet "geeky" behind us evermore. Besides, Casey Reas has recently transcended those technical hurdles in a stunning fashion, by writing an influential software program called Processing that enables and facilitates a wider gamut of artists to create their own projects and designs on their computers. It has many possible uses, it's free, and it's a very important step in the continuing evolution of digital art.

For the rest of us, loading these apps onto your iPad converts it into an ambulatory art gallery, your own curated, portable, shareable, interactive museum. Truly this is a new kind of ownership and display of works of art, housing the New Ludics that I mentioned at the outset. This is art that you not only own, but carry around with you. My apps cohabit nicely with the John Whitney and Len Lye movies that I reformatted from my DVDs, my collection of Luciano Berio string quartets, and my PDFs of Metropolitan Museum exhibition catalogs. We all now have the potential to turn our iPads into cultural centers.

About the only "devil" that some of these artists have pacted with is the iTunes App Store, which imposes certain standards for the display and marketing of these pieces (many of which are offered free). In return, the App Store does not quite seem to know what to make of these creations. The artists choose the general store heading under which to offer their apps, but the headings that Apple offers are almost comically wayward: Some of them are filed under Entertainment, some are called Lifestyle (whatever that means), some are Photo and Video apps, two are filed under Music, and one is even Educational. How about this: Let's be revolutionary and just call them art.

Art historian Patrick Frank is author, most recently, of the 11th edition

of Artforms: An Introduction to the Visual Arts. He lives in Venice, California.

|